The Values Gap

America is an exceptional nation

There are few phrases in American diplomacy as cliché as talk of “shared values” with other Western countries. Whether it’s in reference to relations with Britain or Australia, Canada or Germany, France or Israel, American elites never fail to raise this putative point of overlap. Whenever they begin to brush the surface of which values America shares with the rest of the developed West, the only ones identified are vague aspects of any country with a liberal democratic political system, such as voting, and maybe celebrating respect for gay rights for a month annually. However, democracy is a procedure, not a value. Liberalism contains values, but its implementation varies greatly. Once you delve into the details it becomes apparent that the US is an outlier in the developed West in its political norms and attitudes.

Americans are exceptionally desensitized to violence, uniquely accepting of collateral damage and negative externalities, relatively open to chaos, and relatively religious. Moreover, American society is unfathomably saturated with racial politics. Once these points are factored in, it becomes obvious that America’s norms and values diverge sharply from those of Europe and the Commonwealth countries. The only part of the Western world where people appear as habituated to the above list is in parts of Latin America. Even though the US is in cultural terms (clothing, humor, language, food, holidays, etc.) practically indistinguishable from Canada and not unlike the rest of the Anglosphere, what Americans are used to politically is largely outside the mainstream in Europe and the former Commonwealth dominions.

The late former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser summarized the extent of the axiological separation between his nation and America in his book Dangerous Allies:

There is a huge gulf in our value systems. While Australians believe that, for Australians, this is the best country in the world, we do not proclaim exceptional privilege and virtue for ourselves. We do not claim that we are endowed by God to bring justice and peace to the world. We do not automatically assume that what works in Australia will work elsewhere, or that the way we do things cannot be improved by learning from other nations…

The fact that we have a common language with the United States masks the depth of the divide between our value systems.

This doesn’t mean that America’s values are worse than those of these other countries, nor does it mean that they’re superior. Every country must go through its own development and come to have values that reflect their specific conditions, histories, and needs. Nonetheless, this values gap implies that a foreign policy driven by “shared values” has a misguided foundation. It needlessly makes enemies out of countries that may have no desire to undermine Americans’ ways of life and promotes the false notion that entire societies can be refashioned in America’s image on the grounds that it has been done before.

The violent crime rate in American cities exceeds those of the major cities of Western Europe, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Americans accept the fact that there are large swaths of major metropolises where tourists aren’t supposed to venture because crime is normal and expected. They even seem surprised when they spend time overseas and learn that it’s possible to take a stroll at night in an urban area without fear of being robbed or assaulted. Likewise, high profile mass shootings that enter the national news cycle grab some attention for a bit but seem almost banal and quickly lose coverage and sometimes even vanish from the public memory entirely.

The fact that drive-by shootings and other gang violence occur across the country regularly doesn’t even cross most Americans’ minds. I doubt that any other advanced Western country would tolerate the scale of violence Americans have and conclude that the solution is to bar police from forcefully intervening in real time while a crime transpires or that the solution to a Walmart being shot up is to loosen legal restrictions on firearms. Regardless of whether these prescriptions are correct or not, they’re uniquely American. Americans’ acceptance of high crime as a mere fact of life puts Americans closer to much of Latin America where people endure even more egregious levels of violence.

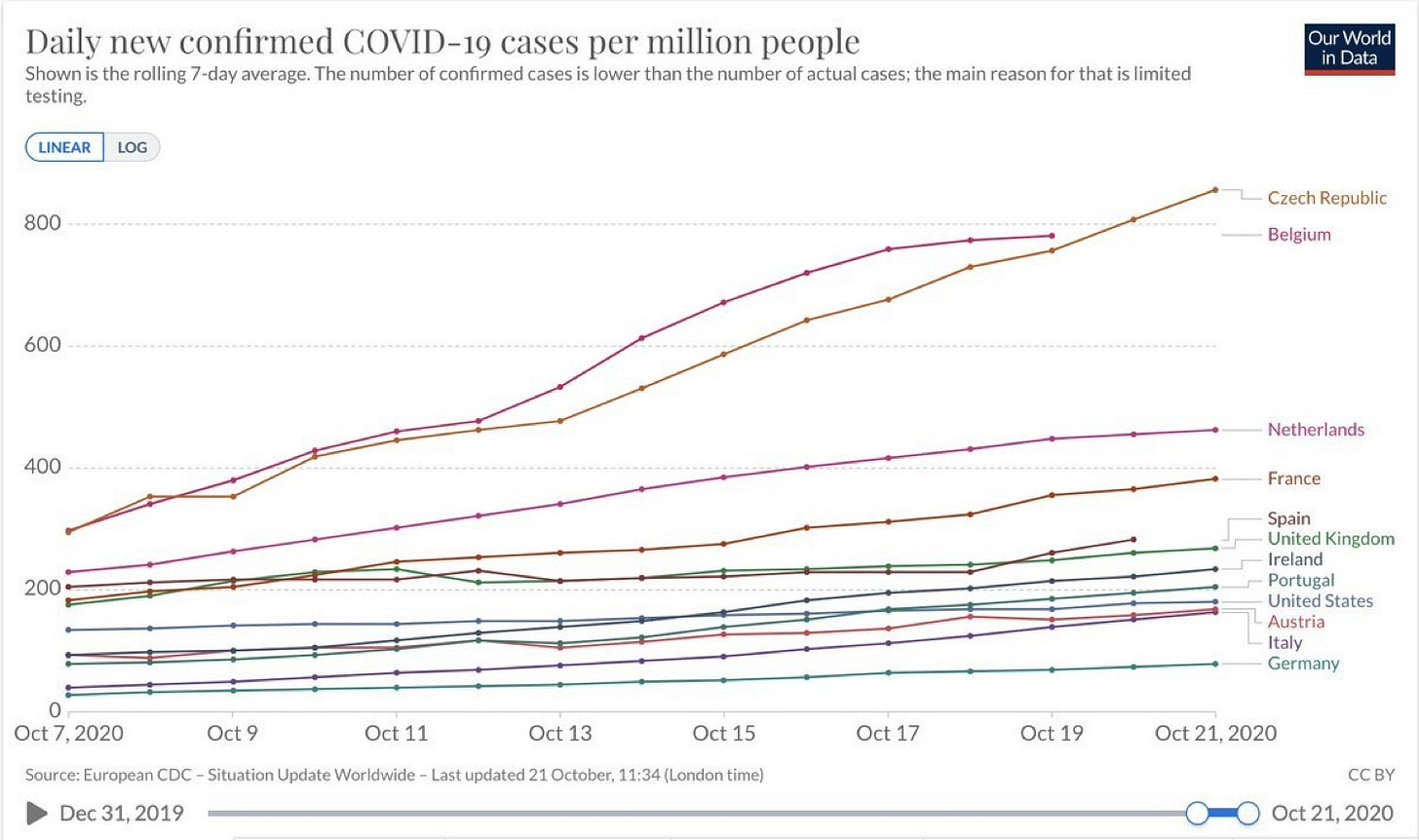

In addition to thinking of violent crime and shootings as just another part of society, Americans countenance collateral damage and negative externalities as the unavoidable cost of everyday life. The rest of the developed West has a safety-first mentality, whereas America has what critics might term social Darwinism or ethical egoism and what proponents might label a respect for autonomy, freedom, and God-given rights. What I mean can be seen with the pandemic response. Despite differing strategies before the vaccine rollout, America and the rest of the non-island Western countries performed similarly. Although America had more total deaths, on a per capita basis it didn’t fare particularly poorly contrary to what is sometimes suggested.

Nonetheless, by the time everyone who wanted the vaccine had received it, America was having far more deaths and had a noticeably lower vaccination rate despite a faster rollout. Why? Most parts of the country opposed requiring the COVID vaccine (even though they mandate a litany of other vaccines), and people began to behave as they had prior to the pandemic. Personal autonomy trumped public safety. People simply accepted that there would be collateral damage if people returned to normal life without vaccination and saw it as judgmental and intrusive to dictate people’s medical decisions on their own behalf. Similarly, Americans move on after a high-profile shooting as discussed previously. Elsewhere, the government seizes people’s weapons as the Howard government did in Australia after the Port Arthur and Monash University shootings and as Jacinda Ardern’s government did in New Zealand following the Christchurch massacre. Swift and lethal violence against sizable numbers of people in a single killing spree due to firearm ubiquity is no more than a negative externality in the American psyche. Even when Donald Trump was shot on live TV, there was minimal chatter about controlling access to weapons, and the story mostly exited the public memory within weeks.

This isn’t to say that this “If you die, you die” mentality is wrong. There are perfectly cogent arguments in favor of permitting people to make terrible medical decisions for themselves, like refusing a vaccine, rather than coercing everyone around you to obey rules, such as sitting in a closed cylinder with your face covered (unless eating or drinking!). It’s simply an observation about American attitudes and how they differ from countries that allegedly share fundamental values.

Americans are also habituated to massive disorder in the form of rioting. Rioting occurs elsewhere as seen across France in the summer of 2023. Yet, the response differs drastically. America’s response to its riots in the summer of 2020 included police reform bills, the slashing of municipal police budgets, and proposals to introduce a new federal holiday by both presidential candidates. In France police unions released public statements deriding their rioters as vermin, and the left-wing mayor of Paris stated that “Nothing can justify violence.” Then-presidential candidate Joe Biden’s team paid bail for people arrested in Minneapolis during the mayhem. President Trump retreated to his bunker as disorder enveloped Washington, DC in June 2020 instead of quelling the chaos. Half a year later, he incited a riot at the US Capitol, which resulted in his second impeachment, and yet he managed to get elected again in 2024 with the popular vote.

Another form of disorder is speech. America is among the only countries that genuinely protects freedom of speech. Most other Western nations criminalize hate speech to protect public order and purported rights to psychological safety. Some might object by pointing to limits on speech in America, such as laws against libel and fighting words, but such an objection equivocates the definition of speech. Speech in the context of classical liberalism refers to the content of political opinions, while speech in the context of American legal restrictions refers to the uttering of words. It is illegal to utter words in certain contexts in the US, such as following someone around and shouting into his hear or defaming a coworker. Nevertheless, the government cannot directly censor the content of political opinions as long as they are conveyed without breaking some other law. By contrast, most of Europe and the British Commonwealth fine or in some cases even jail people for holding or promoting certain political opinions even when there is no harassment, instigation, defamation, or call to action involved. For example, Germany fines people for chanting “From the river to the sea” since they classify opinions that deny Israel’s right to exist as hate speech. In America one can be arrested for harassing a Jewish pedestrian with calls for Israel’s destruction or for plotting to take specific violent actions against the Israeli embassy, but simply arguing in a public forum that Israel has no right to be a country is protected. Most countries have decided that free speech is not worth having because it engenders chaos and enables bigots, but Americans are again more likely to prioritize individual liberty over security and order.

In terms of religion’s influence on society, Americans might feel more familiarity with countries such as Erdogan’s Turkey than with the “desert of godlessness” that is modern Europe. I recall in a 2016 primary debate that Marco Rubio pivoted when asked a question by invoking his loyalty to Jesus Christ. The late former French President Jacques Chirac indicated in his memoirs that George W. Bush considered his invasion of Iraq to be a “quasi-mystical mission that he felt was incumbent upon him.” Similarly, President McKinley claimed that God suggested to him in a dream that the US should annex the Philippines. US presidents swear their oath on a Bible and regularly proclaim, “God bless America.” We know many Americans take this claim literally since there is a history of American religious leaders who frame their country as a “New Jerusalem,” and Rick Santorum described America as “God’s favorite nation.” Much of American support for Israel (particularly among Republicans) is a consequence of theological doctrines. Ben Carson proposed tithing as a tax policy during his 2016 run for the Republican nomination, and large swaths of the population homeschool their kids for religious reasons.

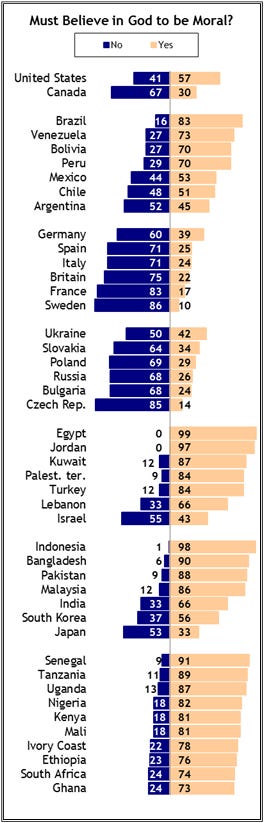

By contrast, other Western countries routinely elect religiously unaffiliated presidents or prime ministers (Boris Johnson, Emmanuel Macron, Alexis Tsipras, Anthony Albanese, among others). In 2007 the majority of Americans responded that they would not be willing to vote for an atheist (now a majority say they would, but it remains relatively low). Until very recently (charts below), Americans were significantly more likely than other Westerners (excluding Latin Americans) to affirm that belief in God is necessary to be moral (not even that God is necessary for morality to be objectively grounded, just for an individual to be moral). It is thus unsurprising that the heads of government in Spain and France would issue statements raising concerns about the revocation of abortion as a constitutional right at the federal level in America (never mind that their abortion laws are not that unlike Mississippi’s, the state whose law prompted the Supreme Court case) since Christian ethics are bound to play a smaller role in their countries than in the US. Religion in politics may ironically result from America’s secular constitution. The fact that the First Amendment both prevents the establishment of a state church and prohibits the government from interfering with the free exercise of religion means that religious organizations must work for their money (which makes the populace more interested in religion since it’s marketed to their tastes) and are able to provide input on public policy (since barring people from using religion to shape politics would violate their free exercise of it as well as their freedom of speech).

The final area where American values are dissimilar to those of other post-industrial Western countries is in the realm of identity politics. It is impossible to live in America for a full year without encountering diversity initiatives, ethnic history months, or people asking about your ancestral heritage. If you walk through a bookstore, you inevitably stumble upon a section with a sign saying, “Celebrating and amplifying BIPOC voices.” Google’s homepage changes to let you know that is May is “AAPI” Heritage Month. Political rallies are filled with signs saying, “Latinos para Trump” and “White dudes for Harris.”

I remember once talking about music with a Frenchwoman, and I mentioned a French artist and the fact that his family was Congolese. She told me that in France everyone is just French, unlike in America where people are hyphenated. People might say they are a Frenchman of Congolese origin, but it lacks the bureaucratic connotation of American racial and ethnic categories. Even countries that collect census data on ethnicity, such as the UK, seem to be less saturated with identity politics. At American universities, students and faculty receive emails from administrators indicating the institution’s support for “vulnerable and marginalized folks” (i.e. racial categories invented by the federal government for legal purposes) during times of moral panic driven by the press, such as the “Stop AAPI Hate” craze of 2021. Such moral grandstanding does not occur at most country’s tertiary education institutions. In the internet age other countries have become as reverent of LGBT pride as coastal America, but this is a weaker form of identity politics than race.

On a side note, it seems paradoxical that America is simultaneously quite religious while also being the first country to fly the rainbow flag. This is easy to reconcile because America is so sharply divided and always has been. The US took longer than various Western countries to legalize same-sex marriage federally, but Massachusetts was among the first jurisdictions in the world to do so. America’s left is more socially progressive than the left elsewhere, while America’s right is slower to adapt than the right in most countries. The existence of such extremes partially explains the chasm in values between the US and the rest of the post-industrial West.

Given the gulf in values between Americans and other non-Latin American Westerners, why do American leaders routinely speak of common values? My explanation is that American elites tend to have values that more closely approximate those of other Western elites rather than those of the rest of their compatriots. Most Americans with advanced degrees, especially from prestigious institutions, favor managed democracy and secularism over rampant freedom at the expense of safety and piety. They would prefer a constitution that enshrines a parliamentary system, limits speech in favor of positive rights, and protects the state from religion instead of protecting religion from the state. The exception is racial politics, where American elites’ attitudes seem to diverge from both other Western elites and from many ordinary Americans. Nevertheless, Americans who dissent from the elite consensus can rest easily knowing that it’s likely their country’s values will remain exceptional among advanced Western nations given the tendencies of the Supreme Court.