The press has a propensity to label the trends within the right’s foreign policy debate as “isolationist” and a deviation from previous tendencies on the right. The historical record belies this claim and reveals consistencies between conservative foreign policies across the decades. I conceive of conservatism as an adaptive attitude that grounds its proponents within the confines of reality—the world as it exists—in contrast to radicalism—an attitude that seeks to refashion the world in conformity with an ideological vision. I argue that in the realm of statesmanship this implies accepting the international system as it exists and pursuing policies that aim to egoistically serve the national interest, unlike statesmanship that seeks to craft a new international system based on a Wilsonian vision. I then use the Vietnam War and Iraq War to illustrate the features of conservative and liberal thinking on foreign policy in practice. I conclude with a series of guiding principles for a conservative foreign policy and a word of advice on the renewed need for conservative statecraft.

The Meaning of Conservatism

Conservatism in the US is strongly associated with object-level politics. In other words, American conservatism is directed towards the achievement of a series of policy goals to advance a vision of human flourishing. Hence, it can be labeled a political ideology, if ideology in the political context is defined as a comprehensive account of what ends politics should seek and what social and institutional arrangements must be created to reify such ends. Hence, American conservatism, paradoxically, isn’t purely conservative. Rather, it would be more apt to refer to it as nationalist libertarianism infused with Christian ethics.

Conservatism properly understood is the rejection of ideology in favor of reality. This might sound like a smug rhetorical ploy to verbally discredit the left and any other political opposition, but it in fact captures the nature of the conservative mind without bias once detailed. Radicalism presents an ideal, and its proponents organize politically to reshape society in that ideal’s direction. Society is perceived as fundamentally flawed because it fails to conform to the moral and anthropological commitments the radical holds. The most egregious cases of radicalism are the totalitarian movements of the previous century. However, more benign forms of radicalism have existed, such as the Wilsonian dream of an institutionalized international community supranationally governed through collective adherence to accepted principles enforced by sanctions. This idea inspired the US policy of unconditional surrender towards Imperial Japan, which expanded Japan’s war with China into a war across Asia and the Pacific and unleashed catastrophic suffering on Japan and its citizens for the purpose of refashioning their country.

Contrarily, conservatives begin with the assumption that the society they’ve inherited, and its accompanying institutions, are ultimately just and desirable. Therefore, conservatives reject attempts to remake social institutions in the service of ideological ends and instead operate within the confines of existing incentive structures in order to secure the possibility of continued prosperity. The political projects of conservatives and radicals thus start from conflicting assumptions—radicals conceive of their society as a problem whose only solution is its reinvention, whereas conservatives perceive their social institutions as delicate motors for the otherwise unnatural success of their society and thus repudiate disruptions to them.

As a result, the utopias that radicals of the same stripe envision tend to resemble each other across borders and epochs, while the preferences that conservatives have tend to vary based on locale. A Marxist-Leninist in theory wants the same economic and political system regardless of whether he’s a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1923 or of the Vietnamese Worker’s Party in 1956—a system of distribution that extracts from each according to his ability and rewards to each according to his need in a classless worker’s paradise. A libertarian in Alabama is as committed to a nightwatchman state as one in Russia, and the maximally constrained government they both advocate can be transplanted to any place at any time. This explains why ideologues in unrelated settings embrace the same symbols. For instance, Argentine president Javier Milei posed with a Gadsden flag since it has evolved into an emblem of libertarianism outside of its original ecology in eighteenth century America, and anarcho-communists around the world rally around a black and red banner.

By contrast, the object-level contents of conservatism vary across societies and can even be diametrically opposed to each other. American conservatives endorse a ruggedly individualistic laissez-faire approach to the economy and social welfare, rigidly oppose abortion and euthanasia out of a thinly veiled commitment to Christian moral precepts, and are skeptical of the public education system and restrictions on civilian firearms ownership. This is an odd set of positions to bundle together, as the underlying moral psychology can appear inconsistent since it displays a reticence to trust the state in some areas while submitting to it in others. Conservatives in different societies stitch together alternative perspectives. For example, French conservatives eschew American conservatives’ distrust of public education and instead see it as a source of national unity, and they reject the religiously infused aspects of their US counterparts in favor of an aggressive secularism to temper multiculturalism. Conservative politicians in Korea have become receptive to pro-natalist policies, and those in Japan narrate the history of their country’s war with America in a form more likely to find a sympathetic audience on the American left. This is all to say that what the term conservatism implies about a policy agenda is largely dependent on the particular society under inspection.

This is because conservatism is an attitude of appreciation for and comfort in the foundations of an existing society and its core values, whereas ideologies are packaged sets of defined political ends designed to be applied everywhere in the service of creating a new society whose existence is, so far, confined to the mind. If there’s an underlying psychology to conservatism, it’s an acceptance that what is established and inherited imposes limits on what is possible. The world consists of tradeoffs rather than solutions, and opportunity costs accompany pursuing some priorities over others. Knowledge is dispersed and best applied through decentralized incentive structures designed to sustain what exists instead of being concentrated among elites who can use it to engineer novel social milieux.

Liberal and Conservative Diplomacy

Foreign policy is the realm of political discourse where coalitions and object-level preferences become murkiest. There are hawks and doves on both sides of the aisle, and there have been eras when support for American intervention in the world was the central cause of right-wing politics (the Iraq War) and when the left came to define itself in opposition to America’s preponderance of global influence (the post-Tet phase of the Vietnam era).

Prior to the Cold War, US foreign policy vacillated between the liberal internationalism of progressives such as Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Franklin Roosevelt and the conservative isolationism of paleoconservatives like Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge. Conservative proponents of restraint may object to the term “isolationism” and prefer realism, as the Republican administrations of the 1920s negotiated the Washington Naval Treaty, and President Hoover later promoted a policy of conditional surrender for Imperial Japan, which may be more reflective of realpolitik rather than of isolationism. Regardless, conservatives tended to exercise greater skepticism towards the idea of America sculpting the nature of the international system, while liberals were relatively eager to build a global community. The tendency flipped after the public turned against the intervention in Vietnam following the shock of the Tet Offensive in 1968. 1972 Democratic nominee George McGovern campaigned with the slogan “Bring America Home,” and the right sought to exploit the rally-around-the-flag effect. Hence, the likelihood of the GOP being interventionist and the Democrats the opposite (or vice versa) isn’t perfectly predictable, and there will always be hawks and doves in each party.

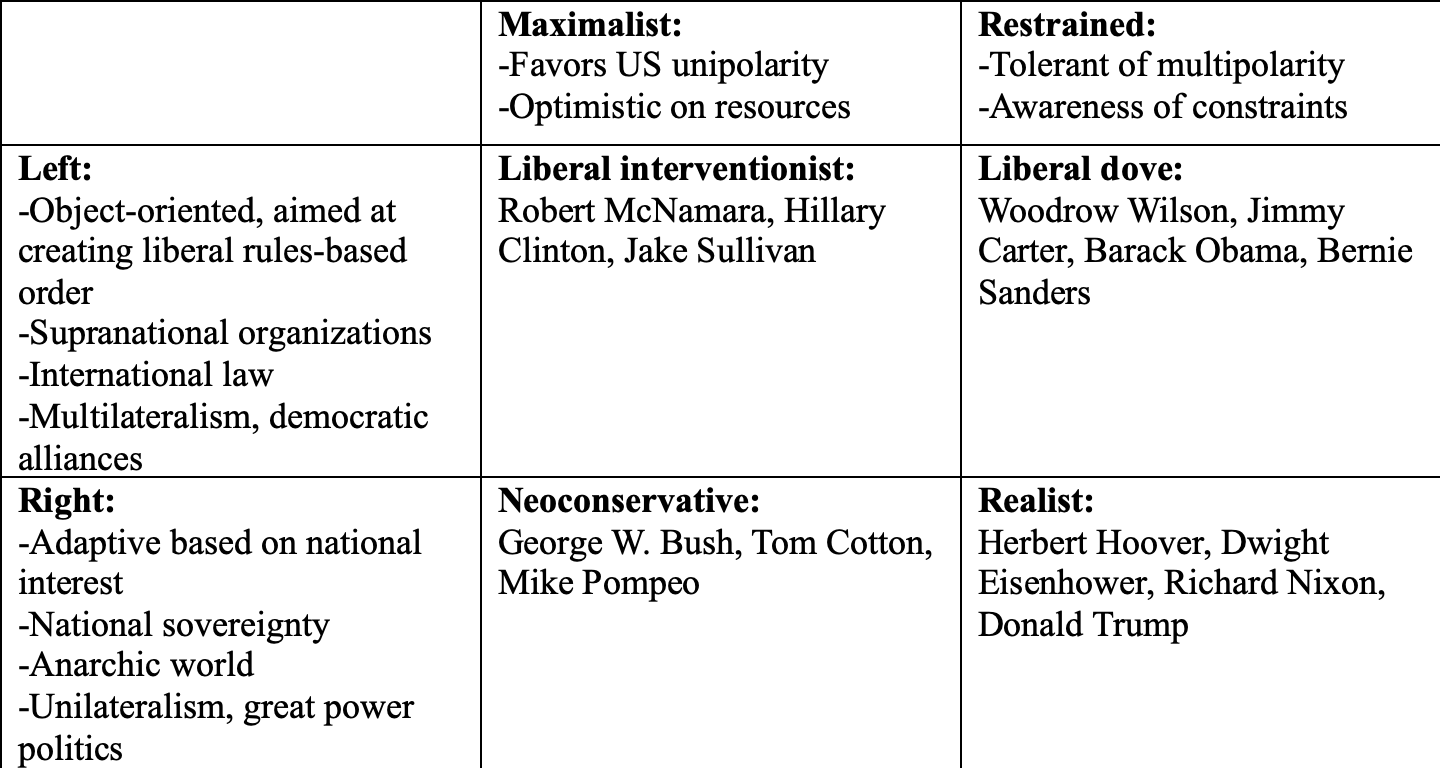

However, the underlying logic behind liberal and conservative hawks differs just as the rationale of their respective dovish counterparts does. Conservatives—whether they be interventionists or isolationists—believe in national sovereignty for its own sake and are therefore skeptical of institutions that appear to undermine it. Liberal hawks and doves, contrarily, believe in the transformative power of international and supranational institutions to usher in a more peaceful world. Hence, although neoconservatives and liberal interventionists are both committed to a grand strategy of liberal hegemony, neoconservatives emphasize hegemony and liberal interventionists liberalism. Neoconservatives view US dominance as a pacifying force because they see Washington as a uniquely benign hegemon and are willing to trade adherence to liberal norms off when it runs contrary to perceived US interests. Liberal interventionists, meanwhile, see US power as a tool underpinning liberal norms and institutions, which would otherwise collapse as the League of Nations did in the 1930s (due partly to the absence of US participation).

Paleoconservative isolationists share with neoconservatives a wariness about ceding national sovereignty but disregard the purported value of American primacy in regions beyond America’s periphery. Their critique of US foreign policy is that it fails to serve US interests and instead threatens democratic governance by ceding authority to transnational decision-makers. Their solution is disengagement from regions deemed irrelevant to Washington’s material interests and the egoistic pursuit of national security and market access. Realists fall between neoconservatives and isolationists in that they have a restrained vision of American foreign policy but see a general retrenchment as imprudent, instead favoring an active but conservative engagement.

Liberal doves overlap with conservative isolationists in their preference for a restrained use of US power, but they agree with their hawkish counterparts in the role of international law, the UN, and multilateral organizations. They criticize US foreign policy for the opposite reason that paleoconservatives and realists do: anti-imperialists believe that American foreign policy is too ruthlessly self-interested and consequently undermines the rules-based order. They see the US as a rogue state whose interactions with the world tend to come from a position of haughty disregard for international norms as well as for other sovereign states, which are meant to be equal in theory. Their objective is for Washington to become more obedient to international institutions and supranational organizations so that it can act as a responsible stakeholder in a liberal international system.

The thread connecting neoconservatives, realists, and isolationists is their acceptance of the fact that the international system is anarchic—meaning that there’s no authority above the level of sovereign states—and their belief that US foreign policy should work within those imposed confines. By contrast, liberals, both hawks and doves, have an ideal vision of the international system wherein democratic states will have equal rights and cede some of their sovereignty as a down payment into a reciprocal rules-based order, and their foreign policy exists for the purpose of moving reality closer to that vision. Consequently, conservative foreign policies are less object-oriented since they’re primarily responsive to the effects of external developments on narrowly defined national interests, whereas liberal foreign policies are purposeful and directed towards reengineering the international system.

Case Studies

The similarities between interventionists and restrainers on the left are reflected in the continuities in the diplomacy of both hawkish and dovish Democratic administrations, and analogous consistencies have been visible on the right across Republican administrations. Progressive Democratic administrations, even hawkish ones, have traditionally been reluctant to violate international law and have typically sought to act multilaterally through organizations like the UN or in concert with other democratic states. Conservative Republican administrations, on the other hand, have been less reluctant to disregard international law when it collides with US interests and have been more prone to unilateral action. There are, of course, exceptions to this pattern. For instance, the Obama administration’s assassination of Osama bin Laden was technically a violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty, and the Clinton administration stepped beyond what the UN had authorized it to do in Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, the general trend has been for those on the left to adhere more closely to liberal international principles and to be more cautious of independent US action even to the detriment of US strategy.

The Vietnam War and Iraq War provide useful case studies. The Kennedy administration decided to support a coup against President Ngo Dinh Diem’s First Republic in 1963 after losing confidence in Diem’s ability to stabilize South Vietnam’s political situation and to lay the foundations for it to realize its democratic aspirations. The result was an assassination, a series of subsequent coups, and a North Vietnamese offensive. The Kennedy administration’s role in creating the mess produced a “you break it, you buy it” situation for America in South Vietnam. After Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in August 1964, the Johnson administration proceeded to begin an air campaign, Operation Rolling Thunder, over North Vietnam and to deploy combat forces to defend South Vietnam in February and March 1965 respectively. While Soviet obstruction at the UN would’ve prevented Security Council authorization for a police action in South Vietnam, the Johnson administration still sought to dress the US decision as a multilateral and defensive action by encouraging US allies in the region (Korea, Australia, Thailand, New Zealand, and the Philippines) to deploy their forces at the invitation of the South Vietnamese government as part of the Free World Forces. That way, the intervention would have legal validity since it was at the request of the host country, and it wouldn’t be perceived as US imperialism because other regional states were contributing to the effort. During Johnson’s tenure, the US refrained from ground operations outside of South Vietnam since Laos and Cambodia were nominally neutral and an incursion north of the seventeenth parallel was ruled out as too risky and would’ve looked invasive.

Nixon was elected in 1968 on the promise of bringing peace with honor to Vietnam through a secret plan involving great power triangulation, escalated military pressure, and Vietnamization. Vietnamization—the transfer of the prosecution of the war from Washington to Saigon—entailed a US withdrawal, and in that sense Nixon’s approach could be interpreted as less bellicose than Johnson’s. Nonetheless, Nixon’s expansion of the air war and ground operations to meet Hanoi at its breaking point was certainly bolder and more escalatory than Johnson’s handling of the war. Hence, it’s less analytically useful to contrast them in terms of hawkishness or dovishness and more helpful to distinguish the relative weight the two placed on international rules and multilateralism. Nixon discarded constraints on action in the territory of nominally neutral states and took the fight to the North Vietnamese in Cambodia through Operation Menu’s bombing campaign in 1969 and through a ground incursion over the border in 1970. Backlash to the latter caused Congress to explicitly ban ground operations beyond South Vietnam’s borders, but Nixon authorized US aviators to lift South Vietnamese forces into Laos to sever North Vietnamese supply lines and decapitate their command in the botched Operation Lam Son 719 the following year.

Nixon displayed little regard for US allies and was far more interested in relations with the Soviet Union and China. Australian leaders only became aware of US drawdowns through public announcements, and the administration considered withdrawing US Forces Korea, which strained relations with Seoul. South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu repeatedly expressed consternation at National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger’s failure to voice South Vietnamese concerns in Washington’s secret bilateral talks with Hanoi and his attempts to hoist on South Vietnam terms that were unacceptable for a peace treaty. Rather than building a foreign policy based on solidarity with liberal democratic allies in Europe, Japan, and Australasia (or pseudo-democratic allies in Seoul and Saigon), Nixon cultivated relations with Moscow and Beijing in the hopes that they’d place pressure on Hanoi to agree to a peace that would allow Washington to maintain credibility by buying it a decent interval between the withdrawal of aid and Saigon’s foreseen fall. Détente with the Soviets and rapprochement with the Chinese reflected a break with the post-1945 Washington playbook in that it was based on the recognition that American power was limited, meticulous calculation would have to dictate the use of Washington’s scarce resources, and the US would have to reach an understanding with the other great powers to shape an international order auspicious to America’s geostrategic position.

The Kennedy administration’s liberal hawks brought America into Vietnam, and Nixon extricated America from the war. However, Johnson and his Kennedy holdovers were unwilling to carry out the war in a manner that would undercut liberal international principles even when doing so gave North Vietnam an asymmetrical advantage. Nixon disregarded such principles with alacrity when they subverted US strategy, and he placed less value on relationships with middle power allies, instead prioritizing those with the other great powers.

The Iraq War offers a worthwhile comparison because it was the project of a Republican administration, unlike the Vietnam War, and therefore reflects a neoconservative, rather than a Wilsonian, logic. Although the Iraq War has now become synonymous with coercive democracy promotion and nation-building, these were post hoc justifications for the invasion. The US adopted regime change in Iraq as policy in 1998 with bipartisan support, and George W. Bush remarked after 9/11 that he suspected Iraq played a role but would have to await evidence before publicly drawing a connection. Vice President Cheney and his political allies were eager for a regime change operation against Saddam Hussein and were uninterested in reconstructing the Iraqi state in its aftermath, whereas the State Department was hesitant about war and more invested in nation-building. This disconnect made for poor planning, and after it was found that, contrary to the Bush administration’s claims, Saddam had no weapons of mass destruction (as International Atomic Energy Agency investigations had indicated), the Bush administration had to camouflage the war in Wilsonian terms to justify it.1

When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, the war became a focal point of political contestation in the following year’s election. Unlike the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, which had near unanimous congressional approval (with the sole exception of Democratic Congresswoman Barbara Lee) as well as authorization from the UN, Operation Iraqi Freedom was controversial at home and lacked legitimacy abroad. Thus, it became an issue for the left to rally against in the election even though some prominent Democrats had initially supported it, including 2004 presidential nominee John Kerry.

Liberals presciently warned that the invasion would undermine the legitimacy of international norms and US credibility as a responsible member of the global community. They criticized the administration for driving a wedge between America and its allies in Paris, Berlin, and Ottawa, as the only US allies to join the Coalition of the Willing were Britain, Australia, and Poland. Obama campaigned in 2008 against the Iraq War and spoke of the War in Afghanistan as the “good war” since it satisfied the conditions for a just war in the liberal psyche. While Republicans would largely come to reject the Iraq War’s justification in the Trump years, their reasons for doing so had less to do with the war’s legitimacy in a liberal international order and more to do with its failure to pass an evaluation of the costs and benefits. Trump notoriously spoke of the need to have “taken the oil” instead of attempting to forge democracy, but he didn’t criticize the inability of the Bush administration to find UN approval.

Conservative Statesmanship

Based on the principles and cases above, it’s natural to ask what a conservative foreign policy would look like in the current context. A conservative foreign policy is one that acknowledges the impact of the anarchic international system on America’s place in the international order and therefore refrains from transformative ambitions. It places greater faith in the ability of the nation-state to act in its own interests than in the capacity for the UN or international institutions to serve such interests. It recognizes that wealth and military resources are the most decisive instruments of national power, not the token support of smaller states or the approval of international bodies without enforcement mechanisms. While not disbanding international institutions, it is willing to accept that there are exceptional times when such institutions can unnecessarily constrain America’s ability to achieve its objectives. It is acutely aware of limitations in the exercise of national power and thus is willing to make tradeoffs when the situation doesn’t permit all of America’s preferences to be realized.

Some general principles that follow from this set of observations are:

1. Seek a stable balance of power and strategic equilibrium with the other great powers over trying to reconstitute a bygone, unipolar, liberal order based on the rules America sets for everyone else

2. Prioritize stable relations with other countries over pressuring them into conforming to American standards of human rights

3. Interact with other countries as peers, not vassals

4. Carefully make use of the limited resources available to America; for example, it’s in the national interest to prevent Russian aggression from succeeding, but it may not be if it comes at the expense of America’s ability to get Europe to build an autonomous defense posture and to keep pace with China’s regional military buildup

The unipolar moment was dead by 2022. China has a larger trade volume with most of the world than the US now, and Russia has been violently carving a sphere of influence while seemingly successfully weathering the storm of maximum US sanctions. The US should embrace a more conservative foreign policy if it wishes to defend its interests in this era of renewed multipolarity.

See Hanania’s Public Choice Theory and the Illusion of Grand Strategy, chapter 6, section on war as a political strategy

Why is Wilson in the "doves" category? Yes, he wanted self-determination, but at the time this was not a "multipolarity" position. It was a "break down the powers of the old world leaving the U.S. as the only large, resource-rich developed country" position. I don't think Wilson deserves the reputation he gets as a "democracy imperialist" but he was kind of getting in other people's business

Didn't read the article btw, so maybe you talk about this. I can't read it because I have to go shit and shower and then do homework